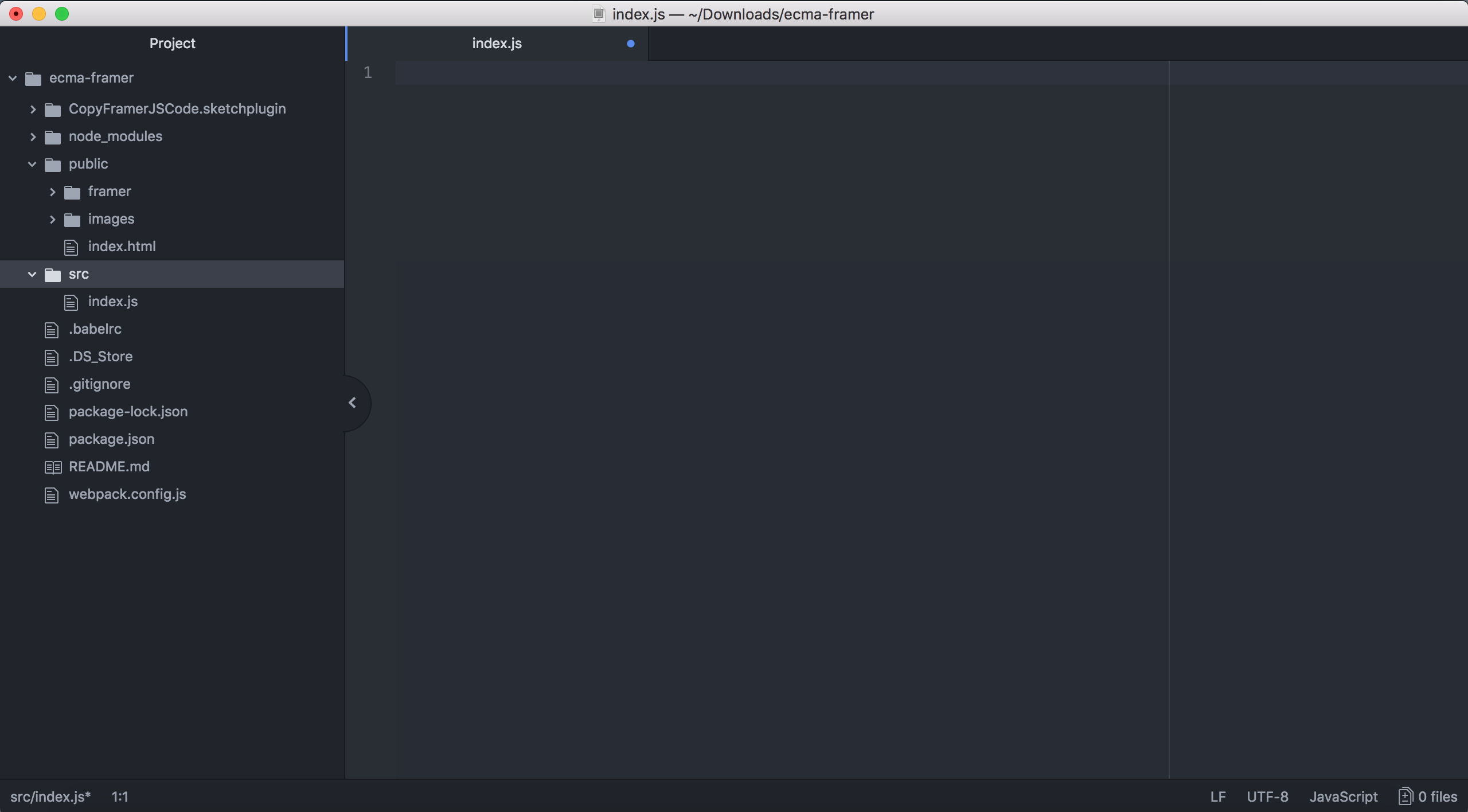

It's time to start programming for real! Fire up Atom or your text editor of choice, and open the file index.js, found inside the src folder within the ECMA-Framer project you downloaded. Now, delete all of the sample code so that we are left with an empty file:

The plan is to make a chat application by the end of this tutorial. This means that we expect our prototype to consist of multiple screens (e.g., logging in, list of contacts, the chat itself). To manage these screens and to be able to easily transition between them, FramerJS provides a PageComponent. Let's start by making one in our index.js file by adding the following piece of code:

var pages = new PageComponent();We'll have to introduce a couple of new concepts here. What happens is that we create a what is called a variable named pages. What a variable does is basically reserve a bit of space (in memory) where we can put whatever we want. So a more simple example of creating a variable would be if I would for example want to store a number:

var mynumber = 123;In programming, we call things such as numbers primitive data types. Numbers are officially called integers, or floats or doubles when they contain decimals. There are also text data types, called strings, and data types that can only be either true or false, called booleans. So for example, I could define some more variables holding these different data types:

var mynumber = 123; // an integer

var mynumber2 = 123.00; // a float or double

var myname = "Jan"; // a string

var is_working = true; // a booleanYou see that each command in JavaScript code always ends with a semicolon to indicate that this is something that needs to be run before resuming with the next statement. Also, anything that you put behind two slashes (//) is called a comment and it is not included when running the code, so you can use it to document what you've been doing.

The main advantage of the use of variables is that we can name our (sometimes complex and dynamic/personalized) data and re-use them later on by referring to them by name:

var combined = mynumber + myname; // results in a string: "123Jan"These examples are still very much simplified, but you will no doubt encounter situations later on where you're glad that variables are around. Going back to our example:

var pages = new PageComponent();Here we create a variable called "pages" and we assign to it a new PageComponent. The PageComponent is what is generally known in programming as an object: a structure that provides certain functionalities to whomever wishes to use them. Generally these objects contain two types of things we can use to our advantage:

- Properties that hold information;

- Functions that trigger interactions or events to happen.

You might be wondering: how do we know which properties and functions are offered by a certain object? Well, in some languages, the editor you will use to write code is able to automatically "learn" this by looking into the object's code. However, JavaScript is super flexible and open-minded in this sense, making it a bit harder to do so. There are still ways, which we will discuss in a later chapter, and well-known objects should come with documentation that allows you to get an idea of how to approach these objects (like FramerJS does).

If we now save the file and run our prototype, you won't see the PageComponent appear yet because we created it with all its properties (such as its size) set to default values, and it also has its default transparent background. Let's change its background color by changing the corresponding property of the PageComponent object we created:

var pages = new PageComponent();

pages.backgroundColor = "rgb(255, 0, 0)";What we did now is take the property backgroundColor of our PageComponent-object that we put in variable pages and assign a new value to it: the rgb-color that has 255 red, 0 green and 0 blue in it. If you save the file, the prototype should automatically refresh and show a red box in the top left corner: that's our PageComponent!

Because we're developing a full-screen app, we want the pages to cover exactly the entire screen (without scrolling). To accomplish this, we can change the width and height on our PageComponent to match those of our screen:

var pages = new PageComponent();

pages.backgroundColor = "rgb(255, 0, 0)";

pages.width = Screen.width;

pages.height = Screen.height;

pages.scrollHorizontal = false;

pages.scrollVertical = false;

Furthermore, we disable scrollHorizontal and scrollVertical. What these do is that they allow you to swipe freely between different pages. For example, if scrollHorizontal would be enabled, you would be able to go from one screen to the other by swiping left or right on the current screen. This is especially useful when you have a tutorial that consists of several steps (screens), and the user can freely switch between them. However, now we want to be in complete control of transitioning between screens, so we disable both of these.

So far we've only been manipulating properties of an object. Functions are accessed in a similar way, with the exception that we add brackets to the end of the function's name, like so:

pages.test();

Now, our PageComponent actually doesn't have a function called test, so this technically won't work, but we'll encounter several examples of using functions later on. While properties essentially only hold information that we can retrieve and change, functions are more advanced. They can have certain inputs and outputs, and do certain manipulations (with or without using the inputs you provide). For example, imagine a hypothetical object math containing a function add():

var solution = math.add(1, 5);

In this example, the output or result of the function math.add() is stored into our variable solution. You see that we provide the add function with some inputs: 1 and 5 (separated by comma). These inputs are called parameters to the function, so we could say that the function add expects two parameters (the two numbers that need to be added together). Parameters can be as simple as the primitive data types we talked about before, but you can also pass objects or variables to the function:

var number1 = 1;

var number2 = 5;

var solution = math.add(number1, number2);

Constructors and dictionaries

Finally, objects have a special type of function that is triggered only once, when the object is first created, called the constructor. It can be used to do some initialization, for example by setting some properties of the object right when it gets created. This is why there were brackets when we were creating the PageComponent before:

var pages = new PageComponent();So, instead of creating a barebones PageComponent and then setting all its properties to our desired values, many FramerJS objects allow us to combine these steps like so:

// Previous solution: setting properties after creating the object.

var pages = new PageComponent();

pages.backgroundColor = "rgb(255, 0, 0)";

pages.width = Screen.width;

pages.height = Screen.height;

pages.scrollHorizontal = false;

pages.scrollVertical = false;

// New solution: providing the desired properties when creating the object.

var pages = new PageComponent({

backgroundColor: "rgb(255, 0, 0)",

width: Screen.width,

height: Screen.height,

scrollHorizontal: false,

scrollVertical: false

});

We can say that the constructor of the PageComponent is a function that takes one (big!) parameter: a collection of all its properties that we want to set right away. This collection is another new construct, encapsulated in curly brackets. This is what is generally called a dictionary (experienced programmers will notice that I take some shortcuts and liberties in definitions here to keep things simple).

The dictionary in programming works just like a physical one: you're looking for a particular term (called the key) and you will end up with the matching description (here called the value). A dictionary is very suitable for describing various details of a certain concept, all in one place. You can mix all kinds of types of values in there, but the keys are always text because that's how we can retrieve values later on. So for example, I could describe a car using only a mix of primitive types:

var my_car = {

num_wheels: 4,

num_doors: 2,

license_plate_nr: "313",

has_roof: false

};

You can now retrieve items from the dictionary in two different ways, like so:

var num = my_car.num_wheels; // num will be 4

var num2 = my_car["num_wheels"]; // num2 will be 4

In our PageComponent example, rather than putting the dictionary into a variable, we pass it directly into the PageComponent's constructor as a parameter:

var pages = new PageComponent({

backgroundColor: "rgb(255, 0, 0)",

width: Screen.width,

height: Screen.height,

scrollHorizontal: false,

scrollVertical: false

});

...the keys are properties of the PageComponent we want to set, such as "backgroundColor", and the values contain those values we want to assign to each property. Most are primitive types: a string describing the background color and a boolean to determine whether we want scrolling to be enabled or not. The Screen object is another special case, it comes with JavaScript and is automatically filled upon running the prototype with several properties relating to your device, such as the width and height of your screen — very convenient if we want to make a fullscreen app!

This concludes our very first coding adventure. Don't worry if all these theoretical concepts didn't fully sink in yet, in due time they will! We'll just move on for now and see how it works when we start building more stuff of our own. Let's move on to building our first screen!